|

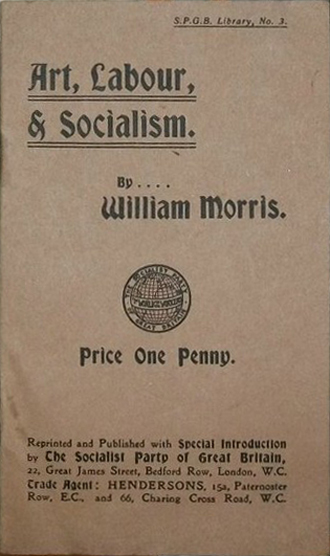

| SPGB pamphlet from 1907. |

Exhibition Review from the May 1961 issue of the Socialist Standard

At the Victoria and Albert Museum in April there was to be seen an Exhibition, Morris & Company 1861—1940. On show were specimens of textiles, tapestries, wall papers, etc., produced by the firm of which William Morris was chief partner and designer. These art and craft products are considered to be the most artistic of their period. But such fine work was not for the homes of the great multitude, as Exhibit 61 (an order book) quite clearly showed.

Looking at this exhibition there was nothing to indicate that for the last 13 years of Morris’ life be worked full speed in the Socialist movement of his day as shown in these words in his essay How I became a Socialist (1894). “But the consciousness of revolution stirring amidst our hateful society prevented me, luckier than many others of artistic perceptions, from crystallizing into a mere railer against ‘progress’ on the one hand, and on the other from wasting time and energy in any of the numerous schemes by which the quasi-artistic of the middle classes hope to make art grow when it has no longer any roots, and thus I became a practical Socialist.”

These words from the chief partner and designer of the Morris firm indicate that under capitalism “Art for the People” is just a phrase but that under Socialism where goods will be produced for use and not for profit Art will be a part of daily life and work in such ways as a free people living in a democratically owned and controlled society wish.

Morris wrote a number of essays and gave lectures on Art and Socialism. Our pamphlet No. 3 Art, Labour & Socialism was a clear statement on the subject and it is possible that before long we may republish it, it having been out of print for many years now.

Ted Kersley