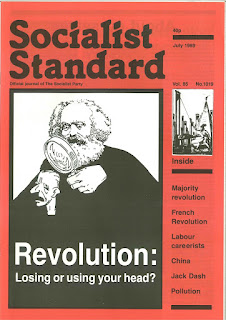

From the July 1989 issue of the Socialist Standard

Up until 1789 France was an Absolutist state ruled by a king who claimed that his total power to rule had been granted him by god. All the top posts in the army, the government, the civil service, the church and the judiciary were reserved for the members of a hereditary nobility. The population was in fact divided into three "orders" or "estates": the clergy, the nobility and the rest – over 95 per cent of course – known simply as the Third Estate.

Relics of Feudalism

The vast majority of the population – some 22 or 23 million out of a total population of 25 million – were peasants who worked and lived on the land. Very few were serfs actually tied to the land or a master. It has in fact been estimated that between 30 and 40 per cent of the land in pre-1789 France belonged to peasants. But all peasants, whether landowners, tenants or share-croppers, had to pay feudal dues in money and in kind to the lord of the manor as well as tithes, payable in kind, to the church. They were obliged to use the lord’s mill, bread oven and wine press rather than have their own and to allow him to hunt freely on their land. And they were tried and judged in a court presided over by him or his appointee for minor offences and all disputes with him or among themselves concerning land matters.

These were all survivals from feudalism, though it would be inaccurate to describe French society on the eve of the revolution as feudalism. Capitalism had long been developing there and in fact many of the lordships of the manor had been bought by rich non-nobles from the towns as an investment for the income this procured them.

Nor was the nobility any longer really feudal. By this time they had become transformed into an exclusive group which, by virtue of their noble status, enjoyed various tax exemptions and a privileged access to the top posts in the state, a fact that was particularly resented by rich people of non-noble origin – the bourgeoisie – who were to provide the leadership of the French Revolution.

This – the upper echelons of the Third Estate, or non-noble rich people – is the easiest definition that can be given of the bourgeoisie. Some were merchants, others manufacturers, still others professional people, in particular lawyers of various sorts. Below them, in the towns, were the sort of people who in Paris were known as the sansculottes, literally ""those without breeches", or people who wore trousers rather than the knee-breeches and stockings then worn by the rich and those who aped them. These were the small shopkeepers and providers of various services, the master artisans and their journeymen who one day hoped to become masters themselves. Those who were condemned to a life-time of dependence on selling their labour power for a wage to a manufacturing employer were relatively few and were concentrated in certain industries and towns. One estimate puts their number at as low as 600,000.

Obstacles to Capitalist Development

Pre-1789 France is best described as a country in which capitalism had been developing within a framework of political and social institutions inherited from feudalism, which had become an obstacle to its further development. The question that then arose was: how were these obstacles to be removed? By reform from above or by revolution from below? Some of the king’s advisers and administrators were aware of what was required. The conscious economic aims of the revolution (see inset) had in fact been worked out by a group of French Rationalist Philosophers who called themselves économistes or physiocrates. They held that there were natural laws governing the production and distribution of wealth just as there were other laws of nature and that governments should let these economic laws operate spontaneously. Hence their slogan laissez-faire which strongly influenced the similar idea put forward by Adam Smith in his Wealth of Nations that appeared in 1776. A number of royal officials, including ministers, had been Physiocrats, but had come up against all sorts of resistance in trying to carry out reform from above.

________________________________________________________________________

Aims of the 1789 Revolution

POLITICAL: To establish equality between all property-owners by abolishing the privileges enjoyed by a section only of them, the nobility. To establish a constitutional government responsible to an assembly of property-owners elected on a restricted, property franchise.

ECONOMIC: To abolish internal customs duties and establish a national market. To abolish guild and government restrictions on entry into particular trades and businesses and establish freedom of enterprise and laissez-faire. To end feudal dues and tithes levied on agricultural property; rent, interest and profit to be the only legitimate forms of non work income.

________________________________________________________________________

Largely as a result of its failure to reform itself, by the 1780s the royal government had got into such financial difficulties that bankruptcy threatened. To raise more taxes it was obliged to call a meeting of a feudal institution that had last met in 1614, the States General in which representatives of the three estates into which society was legally divided met to discuss the king’s demand for further taxes. In August 1788 the government announced the calling of a meeting of this States General for May 1789. In the intervening period the members of the various estates were to meet all over France to draw up a list of their grievances and demands to submit to the king. The rich members of the Third Estate of the towns used the opportunity not just to complain about the tax exemptions accorded to the clergy and the nobles and to call for a fairer sharing of the burden of taxation among the rich, noble as well as non-noble. They also demanded a Constitution that would allow the representatives of the Third Estate to dominate the States General and turn it into an assembly representing the whole "nation". This aim was openly expressed in an immensely influential pamphlet that appeared in 1789 called What is the Third Estate?, written by Abbé Sieyès. Sieyès answered the question by arguing that the Third Estate was everything; it, and it alone, constituted the nation, the nobility being nothing but useless and privileged parasites:

"The nobility ...is truly a nation apart, but a bogus one which, lacking organs to keep it alive, clings to a real nation like those vegetable parasites which can live only on the sap of the plants that they impoverish and blight. The Church, the law, the army and the bureaucracy are four classes of public agents necessary everywhere. Why are they accused of aristocratism in France? Because the caste of nobles has usurped all the best posts, and takes them as its hereditary property. Thus it exploits them, not in the spirit of the laws of society, but to its own profit."

Thus spoke the bourgeoisie when it had a revolution to carry out.

The session of the States General was opened by the King, Louis XVI, in May 1789. The representatives of the Third Estate soon showed themselves to be in a militant mood, in June turning the States General, as planned, into a National Assembly and later into a Constituent Assembly, or a body charged with drawing up a constitution for France.

The Bourgeois Revolution

This wasn’t quite what Louis XVI and some of his advisers had intended and they began to think in terms of dissolving the Assembly. The king dismissed his reforming chief minister and troops were sent to surround Paris. Popular reaction was not long in coming. The bourgeoisie formed themselves into an armed "National Guard" while, on 14 July, the sansculotte crowds stormed the Bastille. Power in Paris passed into the hands of the armed, revolutionary bourgeoisie.

July 14 has traditionally been regarded as the date that the French Revolution, as the seizure of power by the bourgeoisie, took place. Another, perhaps better, case can be made out for 6 October of the same year. This was the date when, following a march of women, accompanied by members of the National Guard, from Paris to the royal palace at Versailles to demand bread, the king was forced to recognise the power and legitimacy of the National Assembly by accompanying it back to Paris. The old royal administration then collapsed throughout France and power at regional and local level also passed into the hands of the bourgeoisie.

In October the Constituent Assembly abolished all internal customs duties. In fact all indirect taxes were abolished. This presented the new regime with a financial problem – how to raise money to finance its activities? – that was solved by the confiscation and sale of the estates belonging to the church. Most church lands fell into the hands, not of the peasants who had been working them, but of rich bourgeois from the towns. The church was not in fact opposed to this measure as, in return, the clergy were to be maintained by the state as civil servants. But the Constituent Assembly went on to insist, not only that the priests should swear like all other civil servants an oath of allegiance to the constitution, but also that bishops should be elected in the same way that mayors and judges were going to be. This proved too much for the Pope who, in May 1791, put an anathema on the French Revolution which still influences the attitude of Catholic historians to the revolution to this day. But its importance at the time was that it meant that the bulk of the Catholic Church went over to the counter-revolution.

Representative Government for Property Owners

The Constitution was finally promulgated in 1791. It provided for France to be a constitutional monarchy, with the king as the hereditary head of the executive having the same sort of powers as the President of the USA. Although it did not remain in force for long it was a model constitution for the rule of the bourgeoisie, as the non-noble section of the property-owning class in society. Its preamble proclaimed in revolutionary terms the complete abolition of the aristocracy:

"There is no longer any nobility, nor peerage, nor hereditary distinction, nor distinctions between orders, nor feudal regime, nor hereditary justices, nor any order of knighthood …"

The Constitution also incorporated the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen that had been adopted by the National Assembly in August 1789. Despite the declaration that "men are born and remain free and equal in rights", the Constitution went on to draw a distinction between "active" and "passive" citizens based on property as measured by the amount of tax paid. To be a simple voter, this was set at a relatively low level but some 40 per cent of the adult male population found themselves without the right to vote (as did all women). But this was not the only property qualification. The members of the legislative assembly were not elected directly by the voters; these latter voted for "electors" who in turn elected the deputies. There was a higher qualification to be chosen as an elector and an even higher one to be allowed to sit in the assembly.

The abolition of the distinction between noble and non-noble property owners and provision for a constitutional government responsible to an assembly of property owners elected on a restricted franchise was in fact the openly declared aim of the French Revolution from the start. It was proclaimed in the Constitution of 1791 and emerged again in 1795 to survive until Napoleon seized power in 1799. Between 1792 and 1794, however, the revolution, under the impact of both an external war and an internal civil war, was to take a more radical turn but one which turned out to be no more than a detour.

The Jacobin Dictatorship

War was declared on Austria, which had taken the side of the overthrown aristocracy, in April 1792 and in July Prussia declared war on France, leading to the invasion of the country by Austrian and Prussian troops. The King, however, continued to maintain contacts with Austria and Prussia. As the invading armies advanced on Paris popular discontent over the economic and political situation broke out, leading to the storming of the royal palace and overthrow of the king on 10 August 1792. France was not declared a Republic until September, after the defeat of the invading armies at Valmy on the road to Paris, but this date marked the effective end of the monarchy. In December Louis XVI was put on trial for treason, found guilty and executed in January 1793. Thus, as in England in 1649, a king claiming to rule by divine right found out the hard way that this was not so.

A new Constitution was drawn up putting power into the hands of a national assembly elected on the basis of universal manhood suffrage. This democratic aspect, however, remained a dead letter as the new assembly allowed one of its subcommittees, the Committee of Public Safety, to assume full powers to organise and mobilise the war effort. After another uprising in Paris at the end of May power passed into the hands of the Jacobins, the most militant section of the revolutionary bourgeoisie whose best-known leader was Maximilien Robespierre.

One of the first things that was done under the new regime was to settle the land question. A law – that of 17 July 1793 – decreed the abolition of all feudal dues without compensation. The principle of the abolition of feudal dues had been proclaimed as long ago as August 1789, but had provided for this to be done by the peasants buying these rights from the lords of the manor. Naturally the peasants were not satisfied and peasant unrest, in the form of refusal to pay and the burning of chateaux and feudal title deeds, continued. The Committee on Feudalism of the various national assemblies was in an embarrassing position because the beneficiaries of feudal rights were not all nobles but included many rich members of the Third Estate.

It was never the intention of those who carried out the French Revolution to abolish the private ownership of land or to break up the big estates of the rich and divide them among the peasants. That would have been a flagrant violation of the "rights of property" which the revolution proclaimed and, under a law passed on 18 March 1793, advocating it was in fact made an offence punishable by death. As far as the land question was concerned, the aim was to abolish the burden of feudal dues on agricultural property. This meant that ground rent was considered to be a perfectly legitimate form of income and the Committee on Feudalism tried to pass off many feudal dues as being a form of ground rent. The peasants, however, would have none of this and, through keeping up the pressure, eventually obtained the abolition of feudal dues in a revolutionary way: by their pure and simple abolition without compensation and the public burning of the title deeds which had granted them. The anarchist Kropotkin in his book on The Great French Revolution regarded this as the revolution’s main achievement.

The rule of the Jacobins is generally remembered for the Terror, though in fact its main action was the prosecution of the war and the successful repulsion of the invading armies. The two were connected since the Jacobin government had to deal with counter-revolutionaries at home working in league with the invading powers. The Terror soon developed, however, into a suppression of all opposition on the grounds of the need for absolute unity to "save the nation".

It was not just royalists, priests and other avowed counter-revolutionaries who were guillotined as traitors, but also all others who, for one reason or another, opposed the Jacobin government on some issue, from leftwing sansculotte groups like the Enragés to moderate but still revolutionary republicans like Danton. Suspicion grew that Robespierre was working to establish his own dictatorship. There was probably some truth in this as Robespierre and his supporters did believe in the necessity of a dictatorship to purge the people of aristocratic ideas and attitudes and to lead them to the Republic of small-scale property owners that they saw as the ideal society, and they did toy with the idea of the dictatorship of a single person to achieve this.

The Jacobins were in fact the Bolsheviks of the French Revolution just as the Bolsheviks were the Jacobins of the Russian Revolution. This affinity was consciously recognised by Lenin and Trotsky and is to this day by their followers, as the following from an SWP publication shows:

"The Jacobins were the only possible leadership capable of successfully defending the revolution. We should defend them against both revisionists and ‘left’ utopian critics" (Socialist Worker Review, May 1989)

A similar position is taken up by the so-called "Marxist" school of historians of the French Revolution, including their doyen Albert Soboul. Their books, and his in particular, remain worth reading but in so far as they "defend" the Jacobins are not a proper nor an adequate application of the materialist conception of history. Applied to the French Revolution, this would seek to analyse the economic factors that determined it rather than to defend or attack the political role played by some or other group or person in the course of it.

Whatever may have been Robespierre’s reasons for justifying the dictatorship of the Jacobin Committee of Public Safety, the bulk of the members of the national assembly (and indeed some members of the Committee itself) supported it as a necessity to win the war, both external and internal, and were ready to relax it once this had been achieved, as it had been by the summer of 1794. This was fatal for Robespierre who was overthrown on 27 July (9 Thermidor, according to the revolutionary calendar) and guillotined with his immediate followers the next day.

The Right to Unequal Property Ownership Re-asserted

The overthrow of Robespierre and the Jacobins marked the end of the radicalisation of the French Revolution and a return to its original aim of establishing a constitutional government by and for property owners. The only difference with 1791 was that this was now to be achieved within the framework of a Republic rather than of a constitutional monarchy. The Republican Constitution of 1795 reintroduced the property qualifications for being an "active" citizen, an "elector" and a deputy.

The Jacobins too had been defenders of the "sacred right of property". Where they differed from the Thermidorians (as those who overthrew them were called) was that they were not prepared to defend the existing degree of inequality of property ownership. For them property ought to be based on work and their ideal was a France in which every Frenchman would own his own farm or workshop and be able to maintain himself and his family out of the results of his own work without having to go out and work for wages for someone else. This ideal, which can only be described (using the term correctly for once) as "petty bourgeois", was an impossible one in the context of the capitalist society that had been developing in France, as was neatly revealed by an exchange that took place in the national assembly in September 1794, at a time when the Jacobins were still in power. After a Jacobin deputy had expounded the ideal of every Frenchman owning his own plot of land and working for himself, another deputy got up to speak on, according to the Minutes, "the material impossibility of transforming all Frenchmen into landholders and on the unfortunate consequences which in any event this transformation would bring". The deputy explained: "Because, on this hypothesis, everybody being obliged to cultivate his own field or vineyard in order to live, commerce, crafts and industry would soon be annihilated". In other words, a non-owning section of the population was needed to supply people to work for wages in capitalist commerce and industry.

But a Bourgeois Republic based on inequality and a Petty Bourgeois Republic based on equal property ownership were not the only two ideals thrown up in the course of the French Revolution. In 1795 and 1796 with Babeuf and the Conspiracy of the Equals another ideal was put forward: common ownership and the abolition of all property, buying and selling and money. The conspiracy never really had much chance of success as it was infiltrated from the start by government spies and probably most of those involved in it favoured the Jacobin ideal of a Republic of small property owners (as well as the Jacobin policy of a dictatorship, which Babeuf favoured too) rather than common ownership and the abolition of all property, but the Conspiracy has left us with a magnificent document, written by Sylvain Maréchal, which we reproduce in this issue.

Political Failure, Social Success

Those who overthrew the Jacobins – the partisans of an unashamed Bourgeois Republic based on inequality of property ownership – were unable to establish a stable regime, mainly because most property owners turned out to favour a restoration of the monarchy and, in the end, a large number of bourgeois revolutionaries, including the Abbé Sieyès who had played such a prominent propagandistic role in preparing the seizure of power by the bourgeoisie in 1789, accepted the military dictatorship of General Napoleon Bonaparte as the only way of ensuring a stable government and preventing a royalist come-back. The seizure of power by Napoleon in 1799, and his subsequent self-proclamation as Emperor in 1804, meant that from a political point of view the French Revolution was a failure: it did not succeed in establishing a "representative government" along the lines of what had been achieved in America and which had been its original declared aim. It did, however, succeed in radically transforming the social structure of France in that all the remnants of feudalism (division of society into orders, feudal rights owed to lords of the manor) and all aristocratic privilege (tax exemptions, exclusive access for nobles to the top jobs in the government, civil service, army and church) were swept away without trace, never to return.

This was a real social revolution which emancipated the peasants from feudal exactions and which freed industry from the shackles of the guild system and created a national market for its goods by removing all internal customs posts and establishing a uniform system of weights and measures. And it opened careers in the government, army and civil servants to new men, of non-noble origin.

The achievement of the French Revolution was to abolish aristocratic privilege but it maintained, and consolidated, plutocratic privilege. After the revolution it was wealth as such and no longer noble status that constituted privilege. In short, it established a capitalist state in which the only distinction between people was the purely economic class distinction between those who owned property and those who did not. It paved the way for the last class struggle in history, which can only be ended by the victory of the propertyless class and the establishment of a classless, socialist society based on the common ownership of the means of production, as envisaged before their time by Babeuf, Maréchal, Buonarotti and others involved in the Conspiracy of the Equals of 1795-6.

Adam Buick