POLITICS

A tax on wealth

Time was when the Labour Party paid lip-service at least to the idea of dispossessing the capitalist class of its wealth. Only a few years ago they were pushing the panacea of nationalisation, that travesty of Socialism, though they were prepared even to dilute this by liberal helpings of compensation.

Now, nationalisation, even of this milk-and-water variety, has become a dirty word. The latest idea is a wealth tax—nothing too sweeping, you understand, an annual levy on say all wealth over £20,000 to bring in perhaps £200 million in extra taxation.

Mr. Callaghan, Labour’s shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer, was deputed to fly the kite. But he was careful not to go too far nor to frighten anybody. ". . . only one person in every 100 would be affected,” he said, pointing out that such taxes on wealth already operated in many countries, including Sweden, West Germany, Belgium, Norway, Holland, India, and Denmark—nothing at all ‘‘revolutionary ” about the idea in fact.

Of course, the idea is not revolutionary. But since when has anybody thought that anything emanating from the Labour Party has the remotest connection with revolution? And, even on the Labour Party's own shallow terms, what feeling can anyone now have, other than contempt, for its latest line?

INCOMES

Who earns what?

If only for the record, the latest income figures from the Inland Revenue deserve mention.

Last year, they report, the number of people earning more than £100,000 a year jumped from 63 to 81. There were similar increases in all the top income brackets. Here is the full table (number the previous year in brackets):

Contrast this with the bottom end of the scale where 1.3 million earned about £500 a year; 2.6 million, £600; and 2.2 million, £700. In addition, another 2.1 million earned hardly enough to pay income tax at all.

There are still people who believe in the myth that incomes are being equalised. These figures should shake them, for they show not the slightest evidence of a trend towards equality.

Of course, some will agree that the details relate to figures before tax and that it is only after this has been deducted that the comparison should be made. Agreed, the gap becomes narrower when this is done. But our “equalitarians” must really be simple people if they think this shows the true picture. Even as regards income, there are still many ways —and not illegal ones, either—of evading the tax net. “Expenses on the firm ” is only the most well-known device for doing this, there are others.

But let us come down to fundamentals. Income is any case dependent on wealth—it is ownership of wealth that really matters and all the wishful thinking in the world cannot wish away the fundamental fact that the pattern of wealth ownership has remained virtually unchanged. Roughly 10 per cent. of the population still owns roughly 90 per cent. of the country’s wealth.

And that is the fact that matters.

BUSINESS

Mergers and takeovers

There have been fairly frequent comments in these columns recently about the growing trend towards concentration in industry. Hardly a day goes by without an announcement somewhere of a merger or takeover. Sometimes the takeovers involve really big business, as with the abortive attempt by I.C.I. on Courtaulds; more often it is the big concerns swallowing up the medium and small fry, or the medium ones taking over their lesser brethren. Mergers tend to take place between equals, to avoid competition between themselves or to make themselves strong enough to resist bigger rivals.

All this is well-known. But just how far has the development gone? Exactly how much concentration is there in modern British industry?

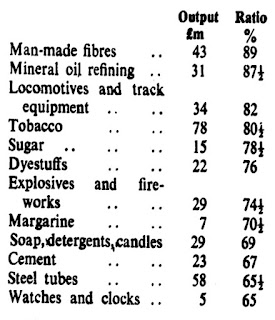

The Conservative Bow Group has recently mads an effort to answer these questions in a pamphlet called Monopolies and Mergers. Taking the three biggest firms in each industry, they have calculated what proportion they account for of the total output. Some of the results can only be taken as broad guides, but here are their findings:

There are really no surprises in the list —artificial fibres, oil refining, tobacco, sugar, dyestuffs, margarine and soap, are all well-known as being mainly in the hands of a few prominent firms.

We should add that the figures relate to 1958 and some of the percentages may actually have risen since then as the result of further takeovers or mergers.

INDUSTRY

Stranger still

In last month’s Standard we mentioned that the French subsidiary of the U.S. Remington office machinery firm had recently been closed down and production transferred to the factory in Holland. This was followed, a few days later, by the closing of the typewriter side of the company in Glasgow and its transfer, again, to Holland. Altogether, a nice example of the international workings of present-day capitalism.

We also discussed in the same issue the surprise and secret takeover by U.S. Chrysler of the French car firm, Simca; adding that 25 per cent. of the shares in the Simca concern were actually owned by one of its competitors, Italian Fiat.

The latest development in the story is the news that the former Remington factory in France may soon be taken over by, guess who? Yes, you’re right. Fiat.

What Fiat intend to do with it if they buy it has not yet been disclosed. But whether it has to do with cars, or typewriters, or something quite different, we can be sure of one thing—there is the prospect of profit in it somewhere.

All we need to really complete the story, of course, would be able to say next month that the former Remington factory in Glasgow had also been taken over in its turn—by Simca.

Who knows? Capitalism is fast becoming nonsensical enough for anything.

Stan Hampson