From the December 1997 issue of the Socialist Standard

Why has irrationality become so powerful an urge at this stage of capitalist development?

Where I live there’s been a noticeable growth of charity shops in town, a more reliable sign of the times, we suppose, than what the politicians tell us. One shop is selling Billy Graham tapes for 30p. My mate buys one (to record over). Then:

“So you like Billy Graham?" His eyes are on full beam.

“Er ... he’s all right like ... I mean, yeah." Nervously my mate coughs, transfixed by those eyes, unable to escape, unable to admit the real reason he’s buying a cheap tape.

“He’s wonderful, you know. I found Jesus through him. We all did. Do you believe in our Lord Jesus?”

"Well er ... no, not exactly ...”

“You will when you’ve heard that. Here, have a leaflet. Take another. Jesus loves you."

He laughs confidently, as do the rest of the staff. Billy has changed all their lives. My mate backs his way out of the shop, making ingratiating noises. The stare never leaves him. Hugely discomfited, like a bird after a near- miss with a tarantula.Why is irrational faith so hypnotic? Why do religious people always cause such acute embarrassment while remaining immune to it themselves? Why is Unreason such a powerful force? A picture emerges: the Christian as ideological terminator, Cliff Richard with an Uzi. You can’t stop them, you can’t argue with them. You just better run.

Speaking of Terminators, I’ve been reading about "technofear" in the weekend rag. Lots of guff about humans turning into machines. Are machines taking over? Is it science fiction or fact? Readawlabahtit!!! What bollocks. If they did, they wouldn’t be so stupid as to operate a system of artificial shortage, would they? If humans learned a thing or two about reason and logic it would be a bloody good thing in my view. In fact, if the world was run by a pinball machine I shouldn’t think anybody would be any the wiser.

Of course technofear exists. Everyone is terrified these computers are going to do us out of gainful employment. Eventually this might well be the case. So-called "expert systems" are a serious attempt to replicate all the diagnostic and prescriptive abilities of a human expert, without his or her irritating tendency to take weekends off, get ill, go on strike or die. Programmers in the trade are expressing considerable surprise at the unenthusiastic response of the human experts whose brains they wish to pick. Some experts have displayed open hostility to the new technology. Next it’ll be sabotage. The programmers are bemused by ail this lack of co-operation. Why don’t these people want to have their expertise enshrined on disk? Why won’t they let us build machines to replace them? They scratch their heads and mutter words like “Luddite” to each other

This is a sorry case of what happens to some people when they overspecialise, I reckon. The programmers have forgotten the plot. Somewhere behind the loops of an algorithm Planet Earth recedes further and further form their view. Finally the light at the end of their tunnel vision goes out.

Capitalism is logical! (erm ...)

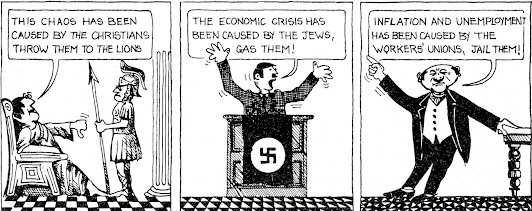

But is it just a case of a few techies doing us all out of a job? I think there’s more to this technofear than that. I think people are afraid of science and reason because they are the gods of the modern age and just look what a mess the modern age is in. In this society, people are increasingly afraid of the internal logic of the system. Because it leads to more pollution, closed wards, less freedom and less security. But this is logic built on sand. If there are wars, it is logical to build weapons. Capitalism proceeds therefore to build weapons. It follows its own logical architecture. It never questions its own foundations, however. War is not logical, but nobody has noticed. It is also possible to build a perfectly logical case that people should starve, if you accept the premise that it is all right for individuals to own food that other people need. That is what our society is faced with. Humans are starving. Capitalism is following the correct logical route. So it must be logic that has brought about this disaster. People are frightened of reason itself because they know from experience that reason levels cities and reason breaks hearts and reason always has really convincing reasons for it all.

In the circumstances, reason begins to look like the poisoned chalice. Religion—a state of benign Unreason—profits from this.There is a powerful sense that Chaos would have been better than the "Order" our logic has created. It is better to believe without evidence, because the evidence points to terror.

Or maybe our culture is at bottom genuinely frightened of logic. Anticipating that we will lose our title of Most Intelligent Species to the incipient binary hordes, we fall back on that ragged and bullet-riddled flag of distinction, the human “spirit”. Not having the faintest idea what a “spirit” is exactly, we only know that machines haven’t got one, so at least we can still crow about being special. We then blithely make a fetish of our own ability to think irrationally, as if this was somehow what made us great in the first place. Besides, illogic is more appealing to our prejudices, given that logic can often take you where you don’t want to go.

And isn’t this irrational flag-waving spirit-soaked species just painfully aware of what a disaster their society is? Doesn’t every newspaper broadcast endless proof of that? Like a supremely bad planetary manager, aren't we convinced that at any moment someone or something is going to come along and give us the sack, and that we deserve it? Underneath it all, everybody knows what a rational intelligence would do about the absolute capitalist system, but nobody wants to admit it.

So why is irrationality so powerful an urge? Perhaps it is nothing but our emotional swell, our hearts beating against our minds, that other force in us which is young as a child and older than all reasoning. The human race is still in the dark and in the dark ages, struggling with its shaky mastery over the planet, an unaccomplished student in the school of thought which it has built for itself. It is now at a desperate stage where it begins to suspect that its skill and cleverness have carried it too far, over the edge and into the abyss. It turns its fear and rage on the rationality that brought it to the very ledge where it now teeters. It’s as if, to recall the myth of Prometheus, we have decided that Prometheus was wrong and Zeus was right. Science has betrayed us, cries a voice in our heads, we should have remained ignorant! So the gift of Prometheus is flung back in his face by people tired of being scorched.

And yet socialists get tired of such knee-jerk anti-rationality. Unreason burned science at the stake for stating the obvious again and again. Nowadays, unable to summon up on demand an auto-da-fe to broil our uncomfortable knowledge, we seem to have buried our heads in “individualism" and telly soaps to avoid thinking at all. Rooted to the spot, like rabbit before the headlights or my mate before the Christian, we stare uncomprehendingly at the chaos bearing down on us, and blame ourselves for its design and manufacture.

We have just missed the whole point of knowledge, that’s all. When Prometheus gave us the fire of reason he neglected to mention that we should never allow it to become the private property of a few “specialists". Private ownership of knowledge is like private ownership of food—it is the conversion of a tool into a weapon, and now that the world is empty of tools and stuffed with weapons we cannot be surprised at people’s wholesale retreat into never-never land, where the bad guys (supposedly) can’t get them. In the world of capitalism, illogic is for many the logical response.

Paddy Shannon