From the December 2012 issue of the Socialist Standard

First of a three-part series, beginning with reorganising society after capitalism.

Regarding the possibility of whether and under what circumstances socialism could replace capitalism, Marx wrote of two prerequisites:

(1) a clear understanding of socialist principles with an unambiguous desire to put them into practice; and

(2) an advanced industrial economy so that free access is technically possible.

As far as the latter is concerned, there's a broad consensus that there's no problem that couldn't be dealt with now, once we've collectively reached the former. The political ignorance of many of the working class has to be the major challenge.

Preparing for change

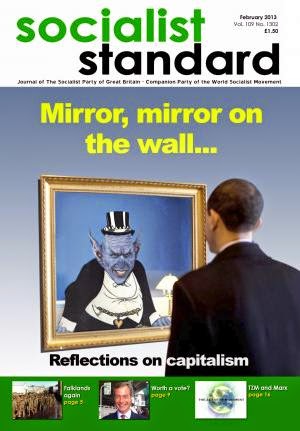

More and more people are recognising that the capitalist monetary solution is not viable for a sustainable world and it is here that we can see the schisms in society becoming deeper. If we look at these schisms through a different lens from the one we are regularly directed towards, we can see that the basic problems aren't actually between 'rich and poor' countries, or even between different levels of earners within countries, that is, not between the producers, the workers, the citizens. Those situations, those schisms, have been manufactured to keep divisions between us. When we come together, we become dangerous –a threat to the established system.

The bigger schism, the real antagonism, is the one between power and the people. What stands out more and more is that:

(1) the capitalist class, through the global corporations (manufacturing, pharmaceuticals, agribusinesses and financial institutions) have dominance over governments, the very institutions that constituents might believe are there to serve the constituents' interests; and

(2) how weak governments are in responding - in fact how complicit they are. (Even a cursory glance at the revolving-door principle reveals the extent of the complicity worldwide.)

The people may fight back, strike or demonstrate, as they did in Seattle's WTO meeting in 1999, at the climate meeting in Copenhagen last December, and more recently in Greece, Ireland, Romania, Spain and other countries, following the ramifications of cut-backs in public spending. People take so much and then, as they reach the final straw, they are compelled one way or another to seek to get their voices heard. By whom? By those who are supposed to be working in the best interests of their societies: their governments. Why don't more people get the irony?

Placebos are offered and sometimes accepted, sometimes imposed, but these placebos are always finance-based, always describing how much a project will cost in monetary terms or how much can be saved if we cut this or delay that. Never are they based on the needs of people.

Reorganising society

Science and technology –scientists and technologists or technicians –have in their hands the knowledge and the wherewithal to take humanity in any direction they choose to take, but like the rest of us they are constrained by the system we live in. They are not directed by the wishes, needs and aims of society as a whole but have to follow the logic of their master, the market.

Everything becomes possible when the tools are in the right hands, the hands of the producers. It becomes a matter of organisation to bring in the new society. There is plenty of work to be done to achieve the satisfaction of everyone's basic needs, but is deliberately left undone as the profit motive dictates. It takes a fundamental shift of emphasis away from the dictates of a small minority to the wishes and needs of the overwhelming majority.

This requires that majority populations worldwide capture the state apparatus politically in order to restructure social decision-making and administration according to their plan. A plan of a totally democratic system, from whose broadest possible base decisions will pass through the structure, representing the widest possible views. Once the motivation for cronyism and corruption is removed by majority will, the best groups of people (best in terms of most fitted to whatever the particular task) could be occupied for the common good in all areas. This bottom-up, proactive, participatory democracy would be used at all levels: local, regional and world. It's difficult to find other expressions away from the hierarchical ones we're so bound up in; the idea here is simply a logistical one, but this particular pyramid definitely has its power at the base with delegates elected to carry forward the message and speak for the whole community.

To attain the stage where the full development of creative human potential is widely recognised as being the goal of life for human beings: this is the change we need. Not achieving parity or possessions, or even getting out of poverty or beating hunger. We have to have a vision far beyond this stage, to see beyond the intellectual paucity that drives current day society to crave the material above the cerebral or philosophical, favouring or craving things above thoughts and ideas. Ending poverty, hunger, treatable diseases and enabling all to have adequate living conditions – all this goes without saying; these goals are all part of what is to be achieved in the period of social reorganisation and will be planned for in full consultation with local communities.

Once decided democratically that we are heading for a socialist world it becomes a much simpler matter. Quite how this will happen is open to conjecture. As expressed on numerous occasions, we have no blueprint. Depriving the capitalist class of the state and its functionaries is the first objective. Once the decision is made, then it becomes a matter of organisation.

Suffice it to say there will have been a period of planning and co-ordination by mass organisations in work places, in neighbourhoods, in educational establishments, in organisations with international links and in civic organisations, which will culminate in the collective and proactive decision of the people to take control over the direction of their lives immediately and for the future. The decision to turn their backs on the system that has failed them over and over in favour of one for which they are ready to work to make happen, ready to work to continue its progress and which will work for them, not against them. With ever-increasing numbers, discussion and debate will have begun to determine the direction of the path to be taken.

No money barrier

It just seems such obvious common sense to consider the cost of everything in human terms instead of putting a price ticket on it. To place the role of social, political, environmental and whatever other decisions firmly with the people, with no need for a pointless monetary budget (the inputs need only be manpower and resources). This will be the biggest shift of emphasis in the change from capitalism to socialism –with far-reaching effects and benefits for both people and planet.

What a much simpler life we could have with this bizarre third element removed from all equations! Why complicate what could be a perfectly simple arrangement? Why tolerate a third element that only confuses and complicates every issue.

Take, for instance, a project to plant trees on a massive scale worldwide – to prevent soil erosion, to sequester carbon, for water retention, to meet the need for fuel-wood etc. –what is taken into account is the cost of billions of seedlings, the cost of mobilising hundreds of thousands of people to do the work, and the cost of paying people not to farm where the land is erodible, where many of the trees would be planted –the total calculated in billions of dollars.

Now you could say the outcomes would be beneficial for many people, ensuring the continuance of farming, better air quality, reduction of CO2 in the atmosphere, preservation of water tables, etc. But surely the simplest, easiest solution –if we recognise it's advisable to plant such numbers of trees –is to mobilise people to collect seeds and grow them, to take cuttings to strike and then plant them on. We would need to know when and how many people to mobilise in which areas, and how many tools would need to be supplied. These are the numbers we need to count. People working in their local communities for the benefit of all, recognising that everyone can't have direct access to the best soil but that all can share the produce from it and also share the indirect benefits of the tree planting initiative.

It's this middle element, money, and the problems arising from it, that prove to be such a difficult concept for many people. In any transaction, and at each and every exchange, it is what's given to and taken from it (i.e. money) that is essential in the capitalist system but absolutely superfluous to what's needed in a system built on communities' needs. What we must get folk to see is that if I work and you work and everyone else works without the complication of money, what will change is there will be no extraction of profit via the surplus labour because all of the labour will be voluntarily contributed. All products and services from our shared labour will benefit the new society as a whole through our system of common ownership and free access. As far as buying and selling is concerned, this exchange will be redundant when we willingly share our common assets, our heads and our hands. What a relief it will be!

Next month: how work will change in a socialist society

Janet Surman