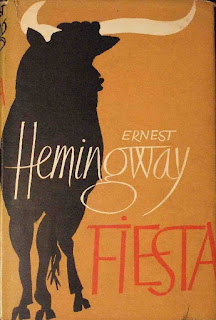

A King was once injured in the loins, and as he lay in his bed, he watched his kingdom decline. It is upon this mythological theme that Ernest Hemingway based his recently republished novel, “Fiesta.” His king is an American journalist, his kingdom, vividly portrayed with neither comment nor condemnation, is the degenerate world of the reckless twenties.

Much has already been written about the political and industrial conditions of this decade. Black Friday and the general strike have been analysed and discussed, and with them the miserable failure, so far as the working class were concerned, of the first two Labour Governments; but so far as the social relativity to economic conditions is concerned, another aspect has been largely neglected.

The first world war had resounding effects upon the social set up of capitalist society. By compromise, or in many cases, by complete surrender, many members of the landed aristocracy had managed to retain a great deal of their wealth and power. Still was it largely their prerogative to send their sons to the universities and thence into the diplomatic corps, the army or the church. Still the sons of the bourgeoisie were found a place in the family business. In both cases the daughters were taught to sing or play, “ finished,” “ brought out ” and used as “ pawns ” or even “ queens ” on the social chessboard.

But the war, which introduced many scientific discoveries, with all accompanying horrors, brought a great step up in production. Thousands of pounds were made overnight. New powers rose in the land. The little fish were swallowed by the sharks. And the war had to be paid for. Taxes rose. The landed aristocracy, living upon ground rents and family fortunes, suffered at the hands of the industrial capitalists. Many of them were uprooted.

The post war world revealed social changes. School, the army, the family estate or business was a sequence broken. The school, alright—the army, too true—but then what? The family estate was now the business of the “nouveau rich” or even the National Trust, and where was the place of the “master’s” son in a vast industrial organisation?

And the position of the daughters had changed as well. This war, dwarfing its predecessors in intensity, had called for the participation to some degree of every human being. The sea barrier, crumbling all the time under capitalism, broke down almost completely. So far as the women of the working class were concerned it merely meant that they became more competition for their jobless menfolk, but for the women of the capitalist class it made them as independent as their parasitic brothers.

This collapse of tradition made their world seem hopeless. Those things that had previously existed to occupy their minds had vanished. Pleasure became their sole pursuit. The social columns were filled with details of extravagant parties. Hostesses were judged by the lavishness and originality of their balls. One achieved passing fame by ordaining that all her guests turn up in baby clothes. The rag-time band, the bottle party, the night club, the stunt, Paris, the Riviera, Eastern tours, was the fad of the layabouts. Drug addiction and immorality reached their highest peak. They dabbled in Freudian psychology and psycho-analysis. Fantastic behaviour was excused as “ self-expression,” perversion as reflexes. “The colonel’s lady and Rosy O’Grady,” as Hemingway parodies icily, “are lesbians under the skin.”

Such conditions and ideas are bound to reflect themselves in the art of the generation. New schools in literature and art portrayed the expensive futility of this generation. The harsh sexuality of D. H. Lawrence, the infathomability of James Joyce, the fatuous writings of unmourned contemporaries, the cubist, surrealistic and futuristic schools of art are all evidence of these trends. “I should have been a pair of ragged claws scuttling across the floors of silent seas ”—these stark horrible words of T. S. Eliot, the era’s major poet, are typical. "I have measured out my life with coffee spoons"—again Eliot.

Forever seeking something new their hungry eyes turned to Russia. What was taking place there? Bolshevik propagandists spoke glibly of the intellectual, of the intelligentsia, of the new culture. Did these words not apply to them? Many of them thought so, and from this womb of jargon emerged one of the most pernicious creations of our time—the left wing intellectual who was going to lead the suffering workers by their noses to what they vaguely referred to as “emancipation.” To further this aim they founded little magazines, not to propagate understanding but to dangle cultural carrots, and under the heading of “reviews” to flatter their own authors’ uselessness.

These were the 1920’s—for the working class a period of unemployment, industrial dispute and lockout; to the capitalist class, especially its younger members, a period of re-organisation and re-settlement. The slump of 1931 put a brake on their activities. So ignorant are they of their own system of society that they were severely shaken and many of them even believed that the system which kept them idle was on the verge of collapse. Many workers, by the way, thought so too. The Socialist Party of Great Britain was not so optimistic. We pointed out that the system would not just collapse, that a force was operating within it that would not only bring about its downfall, but be ready with a new system of society to replace it; that as that force was not ready yet the system would eventually right itself. Time has proved us correct.

But in retrospect we can draw useful lessons from this age. The working class are slated by the bishops and told by the Bible bashers that their licentious habits and immoral practices are the root cause of their poverty. These people do not, or at least do not want, to recognise that it is the working class who are most obedient to the morality of this system of society. After earning or seeking to earn a living they have in the main neither the time nor the energy to do otherwise. It is only when a class is completely divorced, as were they also in ancient Rome, from all useful work that their minds turns to these excesses.

And it is the working class who by their lack of political understanding keep these people idle. Contrast this sterile opulence with your poverty and usefulness. They are linked. Ask yourselves why? The Socialist Party of Great Britain can provide the answer. This is capitalism wherein a small class own the means whereby you live. They neither toil, nor do they spin. You do that! They reap the benefits. The solution? A new system of society wherein these things are the property of all mankind. Under such a system not only would your material needs be satisfied but your culture would be a reflection of happiness instead of misery. It can come just when the working class desire it. So read, learn, realise and band with us.

Overthrow this sterile curse!

Ronald.