Book Review from the March 2010 issue of the Socialist Standard

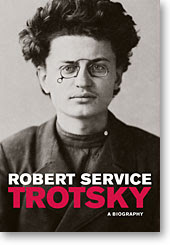

Trotsky. A Biography. By Robert Service. Macmillan. 624pp.

Were Trotsky alive today, he would have the editors of this book shot. It is riddled with irritating errors. Round brackets close square; names change spelling; weird sentences like the idea that Russian radicals “took the bits of Marxism they disliked and discarded the rest” slip through; and apparently Oslo and St. Petersburg lie on the same longitude, 59 degrees North. Macmillan should be ashamed to have allowed this slapdash product into print.

This would not matter except that the representatives of Trotsky on Earth have launched a flurry of chaff to attack this biography of their idol. Forensic hair splitting has been their method, and finding faults, such as that Natalya Sederova (Trotsky’s partner) died in 1962 rather than 1960 as the book claims. This is, of course, a distraction tactic. Hardly any of their reviews deal with the meat of the book.

Peter Taaffe, leader of the “Socialist Party” (formerly Militant) performs the usual Trotskyist miracle of simultaneously denying and justifying the repressive tactics and terror of the Bolsheviks. David North of the World Socialist (sic) website cavils over trivialities, and even manages to accuse Service of anti-Semitism. North also has the lack of originality to describe Service’s text as part of the ‘School of historical falsification’ echoing his hero’s riposte to Stalin.

They don’t address Trotsky’s ordering the decimation of a battalion for cowardice. Or Lenin signing an order for 100-1000 leading citizens of a city to be hanged. The book notes Trotsky’s willingness to use authoritarian methods, and suggests that prior to 1917 he never spelled out what he meant by dictatorship, but that during the crisis leading to the Bolshevik coup d’Etat, he would speak in praise of the guillotine that made opponents of the revolution “shorter by a head”.

Service depicts, with accounts from witnesses, Trotsky as an aloof and self-centred man, who lacked political judgement to help him keep friends close. He alienated many by his manner. He was never, contrary to the received wisdom and dogma of the sects, an organised Marxist. He was a non-aligned member of the Russian Social Democratic Party, who spent the years up to the Great War trying to unify the factions but never joining any. Even when he joined the Bolsheviks, it was as a loose cannon, and that would be part of his undoing.

Service attributes Trotsky’s failure to become the leader of the revolution after Lenin to a lack of will on his part – and claims that any obstacles were surmountable. He suggests that Trotsky was not planning, nor might have been able, to use his position of head of the Red Army to seize power: but that the fear of this motivated his opponents.

What sticks in the craw of the Trots, and threatens the entire ideological edifice of their movement, is Service’s contention that Trotsky did not in policy terms differ from Stalin, and that he had indeed consciously presided over the introduction of a series of show trials of opponents like the ones used by Stalin against Trotsky’s allies. Further, he examines Trotsky’s late claim that the “backwardness” of Russian development was to blame for the “degeneration” of the revolution. In that case, enquires Service, was not the whole enterprise, including all its shed blood, a forlorn waste of time.

Despite the claims of the acolytes, this is not an entire hatchet job, Service freely acknowledges that Trotsky was a great writer and orator, and a brave man in his own personal right. It is, though, a biography, as much a literary form as an historical one, and judgement plays an important part. Service gives his opinion, and is openly critical of Bolshevism and the reader can make up their own mind.

Trotsky. A Biography. By Robert Service. Macmillan. 624pp.

Were Trotsky alive today, he would have the editors of this book shot. It is riddled with irritating errors. Round brackets close square; names change spelling; weird sentences like the idea that Russian radicals “took the bits of Marxism they disliked and discarded the rest” slip through; and apparently Oslo and St. Petersburg lie on the same longitude, 59 degrees North. Macmillan should be ashamed to have allowed this slapdash product into print.

This would not matter except that the representatives of Trotsky on Earth have launched a flurry of chaff to attack this biography of their idol. Forensic hair splitting has been their method, and finding faults, such as that Natalya Sederova (Trotsky’s partner) died in 1962 rather than 1960 as the book claims. This is, of course, a distraction tactic. Hardly any of their reviews deal with the meat of the book.

Peter Taaffe, leader of the “Socialist Party” (formerly Militant) performs the usual Trotskyist miracle of simultaneously denying and justifying the repressive tactics and terror of the Bolsheviks. David North of the World Socialist (sic) website cavils over trivialities, and even manages to accuse Service of anti-Semitism. North also has the lack of originality to describe Service’s text as part of the ‘School of historical falsification’ echoing his hero’s riposte to Stalin.

They don’t address Trotsky’s ordering the decimation of a battalion for cowardice. Or Lenin signing an order for 100-1000 leading citizens of a city to be hanged. The book notes Trotsky’s willingness to use authoritarian methods, and suggests that prior to 1917 he never spelled out what he meant by dictatorship, but that during the crisis leading to the Bolshevik coup d’Etat, he would speak in praise of the guillotine that made opponents of the revolution “shorter by a head”.

Service depicts, with accounts from witnesses, Trotsky as an aloof and self-centred man, who lacked political judgement to help him keep friends close. He alienated many by his manner. He was never, contrary to the received wisdom and dogma of the sects, an organised Marxist. He was a non-aligned member of the Russian Social Democratic Party, who spent the years up to the Great War trying to unify the factions but never joining any. Even when he joined the Bolsheviks, it was as a loose cannon, and that would be part of his undoing.

Service attributes Trotsky’s failure to become the leader of the revolution after Lenin to a lack of will on his part – and claims that any obstacles were surmountable. He suggests that Trotsky was not planning, nor might have been able, to use his position of head of the Red Army to seize power: but that the fear of this motivated his opponents.

What sticks in the craw of the Trots, and threatens the entire ideological edifice of their movement, is Service’s contention that Trotsky did not in policy terms differ from Stalin, and that he had indeed consciously presided over the introduction of a series of show trials of opponents like the ones used by Stalin against Trotsky’s allies. Further, he examines Trotsky’s late claim that the “backwardness” of Russian development was to blame for the “degeneration” of the revolution. In that case, enquires Service, was not the whole enterprise, including all its shed blood, a forlorn waste of time.

Despite the claims of the acolytes, this is not an entire hatchet job, Service freely acknowledges that Trotsky was a great writer and orator, and a brave man in his own personal right. It is, though, a biography, as much a literary form as an historical one, and judgement plays an important part. Service gives his opinion, and is openly critical of Bolshevism and the reader can make up their own mind.

Pik Smeet

No comments:

Post a Comment