From the June 2004 issue of the Socialist Standard

It was the early Sixties. Things were looking good in Northern Ireland. The province was as near to an economic boom as it ever gets; there had not been any serious sectarian rioting since 1935 and an IRA campaign that had commenced on the Border in 1956 was petering to an inglorious end with a statement from that organisation admitting the lack of support it had received from the Catholic nationalists of the north.

The World Socialist Party of Ireland had offices at Donegall Street in Belfast. There we spent a few late nights debating whether or not we should embark on our first electoral campaign. Money was an important consideration: £25 deposit – which, of course, we expected to lose; election addresses, 10,000 with the equivalent of 4 pages in each, around £65; posters, say, £35. The estimates were a headache for a small group. We probably needed over £200. And then there was the work: delivering the Election address, putting up the posters, holding two or three open air meetings every night for some sixteen nights.

There was the big consideration, too. The main core of our small membership lived in the widespread Belfast 15 area which constituted the constituency of Duncairn. It was the only constituency we were in a position to contest. Traditionally, it was a fiercely loyalist area, revered by Unionists because it was the power base of Lord Carson who led the fight against Irish Home Rule with an illegal army (the UVF) pledged to make war if necessary on Britain in order to stay British.

On the credit side there were all those meetings, those posters, the very comprehensive Election Address. Had to be worth it. We sat at our map of the constituency, marking out the sites for our meetings. Nowhere near pubs on Saturday evenings. First meeting of each evening at the hot spots, last meetings in the posher places where bigotry, like family skeletons, is usually well concealed.

The Loyalists would associate us with the Republicans because Republicans often showed their ignorance of socialism by claiming to be socialists. That could be dodgy. There were two small Catholic enclaves in the constituency and there would not be any Catholic candidate. The danger here was twofold: the priests might speak out about “atheistic communists” or we might earn support because the Catholics, like the Protestants, might associate us with Republicanism.

On the first evening of our campaign we left our offices, which were marginally outside the constituency. We had a minibus, festooned with posters and with the single speaker of our crackling public address system affixed to the top. Our first meeting was to be at Adam Street, in a hard-line loyalist area, but to get there we had to pass through part of the Dock constituency, a tough nationalist area represented by Mr Gerry Fitt (now Lord Something-or-Other) where a mob attacked our van in the mistaken belief that we were bent on frustrating Mr Fitt’s anxious political ambitions.

The pitch we had selected at Adam Street was at a corner outside a Brethren Mission Hall. But there was a surprise or us there: the authorities had an audience-in-waiting for us. There was an open backed lorry (they were called “tenders”) fitted to accommodate fourteen or fifteen armed policemen, as well as two police cars and a cop motorcyclist.

Hardly had our meeting started when an irate ‘Brethren’ came out of the hall and shouted up to the speaker about the noise of our loudspeaker. His aggressive manner gave the distinct impression that he’d prefer a ruction to an apology, indeed, he seemed nonplussed when our speaker apologised, made a reference to a clap of thunder and agreed to move our vehicle further down the street. People stood at their doors, obviously not best pleased but there was no active hostility and, when we dealt with the single question that was put to us, about “communism” in Russia, there was even a mild flurry of interest.

After our last meeting, we were packing up to start distributing our Election Address. As we were removing our banners from the vehicle, the officer in charge of the police approached to confirm that the meetings were finished for that evening. Laughingly, he referred to the incident at the Mission Hall and then told us that, within his experience of Northern Ireland elections, our behaviour was unique. We seemed, he thought, anxious to avoid trouble. We emphasised our educational role – and mentioned the integrity of our skulls.

Our revolutionary fervour might have been cooled the following evening for the armed force of the Crown was reduced to a single cop on a motorcycle. In the light of subsequent events, it would be wrong to mention this cop’s name, suffice to say that he seemed at pains to remain aloof and unfriendly towards us.

On the third or fourth evening of our campaign, we held a meeting in a housing estate called Mount Vernon – now a hotbed of militant loyalist paramilitarism where a dog with a Catholic name could become seriously dead. Even back in those more peaceful times, we were somewhat apprehensive, strategically planning our meeting place at a spot from which escape could most easily be facilitated.

In the event, we had no trouble. A few people came out of their houses and flats to listen and, when we came to questions, the meeting lapsed into a question and answer session between one man and our speaker. None of us read any significance into the fact that the persistent questioner was frequently exchanging words with the motorcycle cop who had a one hundred per cent enforced attendance record at all our previous election meetings.

That evening, after we had concluded the last of our meetings, the cop approached one of our members and asked him if we had any literature additional to our Election Address. Whether by virtue of his personality or the nature of his job, the policeman seemed a man of few words but he became quite animated as he told us that he and his wife had discussed the contents of our Election Address the previous night. He didn’t think we would ever get it – Socialism, that is – but, “Jasus! wouldn’t it be great if we did!”

“It was me, you know, who was getting that fella to ask the questions at Mount Vernon”, he instructed us. “You understand that I daren’t openly . . .” Indeed, we understood.

After that we had a very friendly cop accompanying us each evening. He wasn’t an especially garrulous individual but he did talk occasionally and seemed to include himself in our activities when he said “we” – he even got to appreciate our shared sense of raucous humour.

There were three other candidates in the field, representing the Unionist Party, the Labour Party and a Paisley sponsored ‘Protestant Action’ candidate. The counting of votes took place in the magnificence of Belfast City Hall. Worth recording were the words of the Labour candidate, a decent man called Bob Stewart. He enquired about how we thought we “had done” and when we said we had no expectations of retrieving our deposit, he said, “I dunno; your Election Address was the finest piece of socialist documentation I have ever read”. When asked why he had stood in public opposition to us he opinioned that “I don’t think it’s your time yet”. Not too clever perhaps but, as we said, a decent man.

Then there was the highpoint of the evening: we got 824 votes and saved our deposit. We exited the august portals of the City Hall as though we were walking on air – wondering what it would be like after that first fateful election.

But there was another surprise for us. As we approached our van, illegally parked in May Street, there was a motorcycle cop in attendance. “Well . . .?” It had nothing to do with parking and the cop was well off his beat. He was genuinely interested in how our vote had gone and he told us that our total included the votes of himself and his wife.

Sometime later, one of our members had taken his kids to a public park on a Sunday morning. There were very few people about and, of course, in Belfast at that time Authority deemed that their remorseless God would be gravely offended by children playing on Sunday so officialdom locked the swings in the playground. But religious ingenuity had not devised a means of locking the slides so the few children there were presented with an occasion for sin.

Anyway, the motorcycle cop, now in mufti, arrived with his two children and while the kids sinned together on the unapproved slides, their fathers talked. He’d been a cop for seventeen years . . . life was fashioned around the job, mortgage etc. had misgivings now but what could he do? Our member nodded sympathetically.

In the afterwards, some of us saw him from time to time; he remained a traffic cop until the early Seventies when he was shot dead by an IRA ‘freedom fighter’ who, presumably, had an aversion to traffic cops.

By then, of course, freedom fighting had created so much inter-community division and bitterness in Northern Ireland that there was no place within working class areas open to consideration of ideas outside the foul patterns of religious and political sectarianism.

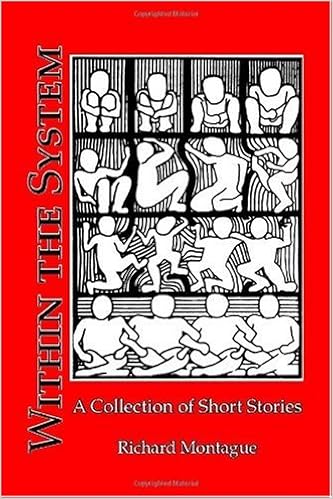

Richard Montague