From the March 2019 issue of the Socialist Standard

‘The One Big Union, therefore, seeks to organize the wage worker, not according to craft, but according to industry; according to class and class needs. We, therefore, call upon all workers to organize irrespective of nationality, sex, or craft into a workers’ organization, so that we may be enabled to more successfully carry on the everyday fight over wages, hours of work, etc., and prepare ourselves for the day when production for profit shall be replaced by production for use’ (One Big Union Constitution).

In late 1918 Western Canadian unionists placed a number of radical resolutions before the delegates at that year’s Trades and Labor Congress Convention. In particular, they wanted the Congress to abandon craft unionism for industrial unionism, but their criticism extended to such difficult questions as conscription, censorship and the war effort. Every one of the proposals was defeated. Before returning home, the western delegates agreed to hold a special western Canadian labour conference in 1919 to discuss ways that they could have more impact on the TLC. By the time the delegates from western Canadian unions arrived in Calgary for this meeting in the spring of 1919 they were no longer interested in fixing the TLC. Instead, they believed the time had come to create a new industrial union that would not discriminate between skilled and un-skilled, foreign-born or Canadian-born workers

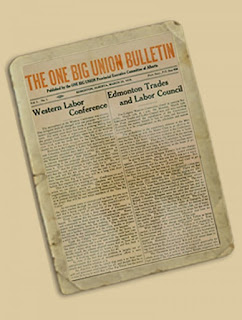

On 13 March a conference of trade union activists was called at Calgary who had grown discontented with the TLC. The 237 delegates who attended agreed to secede from the Trades and Labor Congress of Canada and the American Federation of Labor and to form a new industrial organisation. They adopted the name One Big Union, along with various economic and political resolutions. Delegates called for ‘the abolition of the present system of production for profit.’ A central committee was elected, that included five Socialist Party of Canada (SPC) members and which provided many of the activists of the OBU. However, those from the SPC did not abandon their own project of building the party for an anti-political syndicalist dream. The OBU, unlike the Industrial Workers of the World stressed class organisation rather than industrial organisation. The OBU in Canada was structured more on organising workers geographically than by industry (which caused an early dispute within it). In pursuance of this class policy it did not condemn political action, but rather declared that the only hope for the workers was ‘in the economic and political solidarity of the working class, One Big Union and One Workers’ Party’ (The OBU. Bulletin, 20 December, 1919). The founding members of the OBU were determined to create a union that was opposed to capitalism itself.

‘The OBU was not expected to free the workers from wage slavery any more than the trade union were. There was no question of industrial vs. political as in the IWW 1908 schism. The two were seen as complementary phases of the working-class movement. The One Big Union and the general strike were limited weapons in a battle which was ‘defensive as well as offensive,’ explained an OBU Bulletin editorial.

The concept of the One Big Union was that all workers should be organised in one union – one big union, the OBU. Most notable was the attempt of the Industrial Workers of the World to organise in the United States, Canada, Australia, and other countries. The debate was over whether unions should be based on craft groups, organised by their skill, the dominant model at the time, carpenters, plumbers, bricklayers, each into their respective unions. Capitalists could often divide craft and trade unionists along these lines in demarcation disputes. As capitalist enterprises and state bureaucracies became more centralised and larger, some workers felt that their institutions needed to become similarly large based on entire industries (industrial unions). The One Big Union movement supported the ‘entire industries’ model over the ‘craft groups’ structure:

‘it is not the name of an organization nor its preamble, but the degree of working class knowledge possessed by its membership that determines whether or not it is a revolutionary body… It is true that the act of voting in favour of an industrial as against the craft form of organization denotes an advance in the understanding of the commodity nature of labour power, but it does not by any “means imply a knowledge of the necessity of the social revolution”, Jack Kavanagh, union activist and SPC member, explained. “There can be no question of industrial vs. political. The two are complementary phases of the working class movement” he concluded in the fall of 1919’ (LINK).

Unholy alliance

The weakness of the members of the OBU was not in daring to dream and to act on those dreams, but not realising how many and how powerful the guardians of capitalism were. The OBU would be broken by an alliance of the officials of the mainstream unions, the employers, the federal government and the Communist Party.

Naturally Canada’s various federal and dominion governments were not friendly towards the OBU and most definitely not the employers who would regularly blacklist OBU workers and refuse to negotiate.

The Canadian Labor Congress LC and its affiliate the United Mine Workers was anti-socialist and against militant industrial unionism and the OBU stood for everything it opposed.

Lenin argued against dual-unionism and against the setting up of revolutionary unions so in the Communist Party, in accordance with Comintern instructions, the party-line was to work in the mainstream unions to oust the various labour leaders and this meant rejoining the CLC. The Communists began a campaign of disruption to pressure the OBU members back into the CLC unions, even if it meant destroying the organisation outright. But the OBU nevertheless endured.

The OBU at its peak had 101 locals and 41,500 members—almost the entire union membership of Western Canada. The OBU faced very powerful opponents. Nevertheless, in 1925 the membership was 17,000 and grew slowly throughout the 1920s to reach a maximum of 24,000 members. The year they joined the Canadian Labor Congress the membership stood at 12,000.

Today, union activists continue to strive for collective forms of organisation capable of superseding bureaucracies and cumbersome legalistic procedures. Driven by the same dreams that mobilised the generation behind the OBU, contemporary workers can learn something from the possibilities and pitfalls of the OBU. The OBU did not have all the answers but what they represented was a tendency that was stopped short by so-called revolutionary proponents of Leninism and the reformist apologists of labourism. Who knows what might have resulted had this development not been cut short.

Jack Houston the founding editor of the OBU Bulletin wrote:

‘The O.B.U. was not created out of pure thought, but from the objective industrial situation. Craft unions have grown obsolete… The O.B.U exists not only because some labour leaders determined to bring it to birth, but because the workers would not remain in the old-style unions. This is a fact and not a theory’ (OBU Bulletin Editorials, LINK).

Houston went on to explain in more detail that:

‘The official ‘impossibilism’ of the SPC guaranteed the party’s political purity and proletarian principles, but did not prevent the socialists from participating in non-revolutionary working-class struggles as well. As it is usually understood, syndicalism implies the creation of worker-controlled economic structures within industry, opposition to the use of political parties and the political system as a means to further the workers’ cause, and, finally, the withdrawal of labourers’ services in a great general strike which would topple the capitalist system.’

He pointed out that:

‘The Socialist Party of Canada rejected the idea that a socialist society could be created by workers’ councils or soviets. The SPC did not regard the general strike as the ultimate weapon in the class struggle. They never promoted sabotage as did the Industrial Workers of the World. They sought, instead, to build an inclusive united working class movement as the next stage in the class struggle. They decided to reduce their emphasis upon political action, formerly their major weapon, because the new militancy of the union membership demanded new strategy—a better union movement… Unions would confront the real rulers of society, the owning class, in another way. Socialist Party members understood that a shorter work week and the creation of a new union organization would not topple the capitalist system. But, as a first step, it would provide an example and a base of operations. The object was to continue the education of the worker, to secure badly-needed immediate improvements in working conditions, and, thus, through organization, to further the solidarity of the working class and to prevent premature violence. The workers’ revolt could begin on a regional basis, the socialist revolution must be national, continental, and, ultimately, world-wide.’

We in the World Socialist Movement can envisage a socialist party growing in the future along with many other expressions of working class organisation including trade unions and workers’ councils. We have never stood aloof from the industrial scene and class struggle, as our critics keep repeating until such claims have become an urban legend for many on the Left. However, what we strictly adhere to is that decisions about industrial disputes and work-place agreements are to be made by those directly involved and not by outside-the-union political parties.

ALJO