Tony Blair has used that pathetic excuse for accountability, the television interview (in which two powerful men get to spar verbally before the massed ranks of passive spectating viewers) to float the possibility that he might support a referendum over the Euro soon. It was on Newsnight’s series of interviews where Blair told Jeremy Paxman that he was willing to be remembered as the Prime Minister that took Britain into the single currency. This slight admission, couched in Blairean caveats and obfuscations, was immediately spun by the loyal sheep in the press as a serious indicator of the state of Downing Street thinking on the Euro, a move in the cabinet chess game.

The reason for Blair’s caution is the deep indecision over the Euro issue, not only among politicians, but also among their paymasters in the capitalist class. His position of stating that he will only ever act in the “national interest” (i.e. in the interests of those as own Britain) is merely re-iterating the obvious, until our masters can actually work out what actually is in their interest. Socialists are able to point this out with ease, as we have done several times in the pages of this journal. What we need to do, as well, is observe quite why the capitalist class is itself undecided.

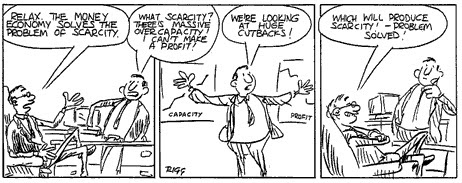

In socialism, Europe will be fully unified by having no money

One of the basic premises of the materialist method of examining society is that ideas simply do not just fall from the sky, but instead develop over time through the actions of people within a particular set of circumstances. That is, human beings make society and its values/ideas, but within the constraints imposed by the actions of other human beings, and the relations between those people. This accounts for the clash of ideas and political opinions not only between classes, but within classes as well. It is the constraints and actions of people within the capitalist system that has produced the running arguments over the Euro.

Contrary to what some groups believe, the capitalist class is not an eternally cohesive, Machiavellian cabal perfectly capable of imposing its will and interest on wider society. It is riven by differences as each capitalist strives to pursue their own economic interest and seize as much a share of the surplus value produced by social production as they are able, by every means at their disposal: legal, political, economic or criminal. The means by which each capitalist secures their share of surplus value determines their economic interest, and each capitalist will do everything within their (considerable) power to secure and enhance that interest. Capitalists who export will want to see an army capable of defending their interests, manufacturers want stability and low wages, transporters want to see low oil prices, etc.

The relations of these economic interests of British capitalists to the EU can be seen by looking at the trade statistics; in 1999 the UK exported £84 billion worth of goods to EU destinations, as compared with £55 billion to elsewhere. Overall, then, 61 percent of trade was to EU purchasers. Further, the UK receives 52 percent of imports from EU member states. Taken on their own, these statistics – other considerations aside – indicate that the capitalist class should favour the Euro in facilitating trade with its major partners. If we look, however, behind the national abstraction of the UK capitalists’ interest, and look instead to the more specific details, then a different picture emerges.

For instance, each statistical region of the UK, bar one, exports the majority of their goods to the EU, some, such as Scotland, send 70 percent of their produce to an EU state. The exceptional region is London. London exports 55 percent of its produce to non-EU destinations. Of course, under capitalism, it is not the size or population of a region that determines its say, but its wealth, and London’s non-EU exports represents 8.15 percent of all UK exports, and 20.7 percent of all extra-EU trade: a total of £11.3 billion worth of exports. Likewise, London imports £21 billion worth of goods from outside the EU, representing 11 percent of import value, and 58 percent of the capital’s import trade. This represents an enormous share of UK trade, and much more than any other single region can lay claim to. (All Stats ‘Regional Trends 2000’, ONS)

This regional disparity is significant for one main reason: when looking at the distribution of national types of industry, it’s clear that over 80% of London’s businesses are in the service sector. Whilst this includes retail firms, it also includes insurance companies and stock brokers, etc. The presence of the City of London region, and the financial and stock exchanges is a big factor in this preponderance of the service sector in the region and many of its exports and imports are a product of international financial transactions, the shuffling of electronic claims to riches from one side of the world to the other, and trading in currencies.

A great many of these London firms, then, will be dependent on being able to extract economic rent from exploiting the restrictions on capital investment caused by currency blocs, whether from pounds to dollars or pounds to Euros. They thus not only have an interest in trading with economic partners other than the EU, but also retaining the pound to protect their income from transaction costs. It is this combination of interests which leads to economic nationalism being prioritised over joining a trading currency zone.

Given the historic and continuing cultural, administrative, and ideological importance of London, the national capitalist class would be unwilling, to say the least, to go directly against the interests of this important sector of British capital. Specifically, a great many of those service firms in London depend upon its centrality to the British state for their business, an interest they would be willing to defend. Add to all this that the minority of exporters to outside the EU still add up to a substantial number who will be willing to side with those who derive their interest from London, and then we begin to unravel some of the reasons why the capitalist class is at a seeming impasse about its potential future economic interests due to its divided internal composition.

This situation accounts, at least in part, for the political situation with regards to the Euro. The Tory Party has traditionally had a strong faction of ideological nationalists whose attachment to the idea of Britain is not contradicted by any personal interest in pursuing the Euro project (indeed, many, as small business folk, will have to bear much of the implementation cost of the Euro). Likewise, the Tories established themselves as a party close to the financiers in the City of London during the Thatcher period and, just as importantly, as being closer to the political, cultural and economic interests of the United States and Wall Street than the EU. These attachments currently enable Labour leaders to try to depict the debate as being about unregulated international finance capital versus domestic industrial/manufacturing capital, playing on old prejudices of ‘wealth producers against bankers’ and attracting support from their allies in trade unions associated with manufacturing.

It is not a question, though, of the ineluctable differences between two essentially different models of capitalism, as Labour hacks will kid themselves, but personal competition between capitalists and the political fallout from this. Furthermore, the consequences of this situation are already beginning to be played out. A week prior to Blair’s statement, Prescott and Byers announced plans for English regional devolution: that is, greater political autonomy being removed from London and spread to regional assemblies as want it. Aside from tapping into the same liberal seam of thought as inspired national devolution to Scotland and Wales, it also provides a means for capitalists in regions outside London to be able to have more control in order to be able to direct their affairs without the interferences by capitalist interests in London. This is in line with the concept of a ‘Europe of the Regions’ by which the supporters of the Europe project hope, among other things, to bypass the influence of those interested in British ‘national’ capital and its historic ties with US finance.

Of course it all goes to show that the nation, and nationalism, are not an eternal and essential characteristic of human beings as some would have it, but are solely a tool for pursuing the further interests of sections of the master class at given points in history. Indeed, the current situation of market interpenetration between British capital and that of its EU partners is itself the result of over forty years of state policy (a fact that some capitalists will be aware of), and if they finally decide against pursuing economic union with the EU, they could equally look around the world for other options.

As such, the working class has no interest in this passing show of inter-capitalist squabbling over the Euro, except to note the spectacle and prepare for the day when there are no more nations to be interested in and money to squabble over.

Pik Smeet